Hello everyone, and welcome to our

third posting for Vulgar Errors/ Feral Subjects, an informal poetry workshop

with a particular focus on writing (and writing through) the abject animal

other.

In last week’s IRL workshop we used the

thirteenth century Latin poem, Vox Clamantis, by John Gower (an

estate satire of the 1381 Peasants Rebellion), as a lens through which to

explore the imaginative animalising of poor others within literature and across

history. We spent some time in “Wolf Land”, reflecting on the ways in which the

destruction of animal populations and native languages are fiendishly

entangled; we discussed the ethics of representation, and whether or not it is

possible – or indeed desirable – for art and poetry to get at the

animal other. We discussed some strategies for disrupting the instrumental

eloquence of what Jonathan Skinner refers to as ‘the monocrop’ of ‘hegemonic

English’, through splicing, collaging, hybridising, glitching and remixing

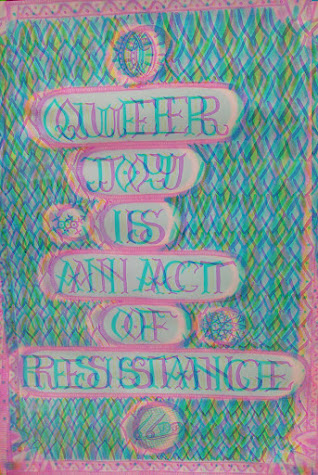

different kinds of authoritative text. Finally, we touched on the feral as an

excess of joy and a form of survival – even resistance. To that end, here is

the wonderful ‘Poetry is Not a Luxury’ by the immortal Audre Lorde:

https://makinglearning.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/poetry-is-not-a-luxury-audre-lorde.pdf

We are definitely going to be talking

more about that! But first I wanted to backtrack a little and think

in slightly more detail about the idea of representation. I’m going to start

with a quote, not from a poem or by a poet (because counter-intuitive is the

name of the game here), but from the novel The Atom Station by

Icelandic author and out-spoken socialist Halldór Laxness. The novel is the

story of Ugla, who moves from the mountains in the North of Iceland to work as

a housemaid for her local Member of Parliament. It's a book about political and

social hypocrisy centred on a decision to sell part of Iceland to provide a US

airbase as an instrument of Cold War Anti-Soviet manoeuvring. The bit that is

relevant to us, is Ugla's meditation on the difficulty of representing

Nature/nature:

In this house there hung, so to speak, mountains and mountains and yet

more mountains, mountains with glacial caps, mountains by the sea, ravines in

mountains, lava below mountains, birds in front of mountains; and still more

mountains; until finally these wastelands had the effect of a total flight from

habitation, almost a denial of human life. […] Quite apart from how debased

Nature becomes in a picture, nothing seems to me to express so much contempt

for Nature as a painting of Nature. I touched the waterfall and did not get

wet, and there was no sound of a cascade; over there was a little white cloud,

standing still instead of breaking up; and if I sniffed that mountain slope I

bumped my nose against a congealed mass and found only the smell of chemicals,

at best a whiff of linseed oil; and where were the birds? And the flies? And

the sun, so that one's eyes dazzled? Or the mist, so that one only saw a faint

glimmer of the nearest willow shrub? […] What is the point of making a picture

which is meant to be like Nature, when everyone knows that this is the one

thing which a picture cannot be and shouldn't be? Who thought up the theory

that Nature is a matter of sight alone? Those who know Nature hear it rather than

see it, feel it rather than hear it; smell it – good heavens, yes – but first

and foremost eat it. Certainly nature is in front of us, and behind us; Nature

is under and over us, yes, and in us; but most particularly it exists in time,

always changing and always passing, never the same; and never in a rectangular

frame (p.39)

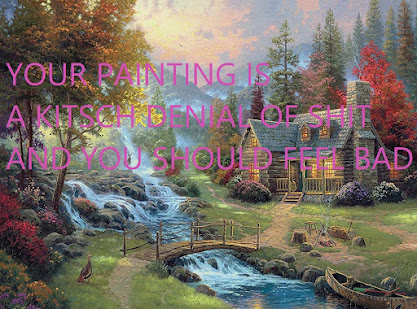

I think the Laxness is referring to a particular kind of twee geography porn

that tries to make the outdoors palatable to people who wouldn't be caught dead

there, but I also think it points to some of the ethical dilemmas inherent in

those ‘rectangular frames’ of canvas and page, however rigorous or

well-intentioned. Specifically the passage thinks about the limits of

representation, everything a cultural artefact is unable to contain or to

express. At its best, poetry is only ever going to be an imperfect sieve for

lived experience; strained through both the unique subjectivity and the

cultural context of its author (and its audience). If we're talking about

writing as an act of preservation or conservation, then perhaps we need to

accept that what we are preserving is only ever partial and

necessarily mediated. We stop its course, arrest its flow, amber it in time and

space. The creative act records and remembers, but it also dilutes and

distorts.

We spoke a bit last week about the way

Nature/ nature becomes hijacked and repurposed in the service of various

political, nationalistic, and corporate scripts. The mountain canvasses, with

which the walls of a prominent political figure are adorned, aren't there

simply because he enjoys looking at mountains, rather they are symbolic of a

particular Icelandic National Character and values; they are being enlisted as

a form of propaganda that has very little to do with the conservation and care

of the real Iceland. In fact the real Iceland is backgrounded,

becomes an absent referent.

If we were looking for a modern

example from visual media that speaks specifically to the animal other, we

might think about Coca-Cola's comic Christmas polar bears (nauseating, I know,

but stay with this). I think during the last brand audit in December 2020

Coca-Cola was named as the world's worst plastic polluter for the third year in

a row. Organisations such as Greenpeace stress this is not merely a litter or

ocean problem resulting from the manufacture of single use plastic, but a

fossil fuel infrastructure issue, a health issue, a social justice issue, and

significantly, a climate issue. While Coca-Cola's anthropomorphised polar bears

are used to promote the brand, the company continues to profit from practices

that destroy that animal's habitat. Potentially worse, recent years have

seen Coca-Cola subtly reposition their brand, so that the polar bear becomes a

vehicle for what environmentalist Jay Westerveld defined - as far back as 1989

- as “greenwashing”, the practice of falsely promoting an organization’s

environmental efforts while spending more resources promoting that

business as green than on engaging with environmentally sound

and sustainable practices.

If we're thinking about the way poetry

itself enlists or exploits nature, we might think not only of the way in which

animal and environmental subjects have historically been utilised towards

ideological ends, but the way in which they have become a metaphorical and

imaginative resource.

There's a potentially useful quote from The Value of Ecocriticism by Timothy Clark (Cambridge, 2019), speaking specifically about the Romantic project, but which is also relevant to the field of contemporary lyric practice:

the reputation of [ …] William Wordsworth as a ‘nature poet’ has become contestable, with the realisation of how a problematically human – and even male-centred – stance structures a poem like the famous ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud.’ For this is concerned with natural phenomena (daffodils in this case) overwhelmingly as a psychic resource, to be celebrated in almost consumerist terms for their contribution to personal growth and pleasure (‘I gazed and gazed, but little thought / What wealth the show to me had brought’ (emphasis added) – a ‘great wildlife spectacle’, in effect. (p.11)

So, will any attempt to frame or transmit the natural world be morally suspect, or doomed to failure? And just to prove our sessions aren’t all rampant Wordsworth bashing, I also offer this from Carol J. Adams book, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (Continuum, 1990): ‘radical feminists talk as if cultural exchanges with animals are literally true in relationship to women, they invoke and borrow what is actually done to animals…’ She writes about the way in which using meat and butchery as metaphors for women’s oppression is voicing our own ‘hog-squeal’ at the expense of the squeal of the literal hog, while acknowledging that male dominance and animal oppression are linked by the way that both women and animals function as absent referents in meat eating and dairy production; that feminist theory logically contains a vegan critique, just as veganism covertly challenges patriarchal society. Patriarchy is a gender system that is implicit in human/animal relationships.

I wonder how we feel about that? And while we're wondering, let's take a look at the mighty Kim Hyesoon. Writing in a lyric essay about her practice, Hyesoon states the following:

In all this time that

I’ve been writing poems, why have I tried so hard to reside within countless

rats, pigs, birds, bears, ghosts, and women?

Did I not write about

them so much as think I was “doing” them?

Why was I,

unbeknownst to myself, using the voices of the dead or the disappeared?

[...]

You can say my poems

are an endless “doing” from the in-between of doing-woman and doing-animal.

These poems are adamantly me, and at the same time are a process of “doing”

that is geared towards what is different from me, or not me—things that are

humble, fragmented, people who seem insignificant. If poets do not involve

themselves in this process or halt it and remain unmoving, they may choose to

call themselves realists but they are neither real nor are they doing poetry.

They are just manufacturers of slogans or metaphors, people who believe the

sentimental is the real. This “doing” follows a line of affect. But the end of

this line is endlessly delayed, and doing-poetry is a continuous flow, like a

river forever open towards a certain direction.

Here’s the full essay:

https://www.kln.or.kr/lines/essaysView.do?bbsIdx=650

And here is Kim Hyesoon, doing poetry:

BLOOM, PIG!

From Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream. Trans. Don Mee Choi (Action Books, 2014)

Has to die even if it didn’t steal

Has to die even if it didn’t kill

Without a trial

Without a whipping

Has to go into the pit to be buried

Black forklifts crowd in

No time to say Kill! Kill!

No time for the blood to splatter onto the shit-smeared walls or light bulbs

No time for the piglets just popped out from the stomach to get skinned and made into cheap colorful shoes

No time for the pale-faced interrogator wearing dark sunglasses to yell Fess up! Fess up!

No time to gamble with terror as if skipping rope, whether I can survive the torture or not

No time to bite the flesh of my mouth as if biting the hand that’s hitting my friend’s cheek in the next room

No time to tie up hands and feet and pull my head back and force water into me

No time to say Mommy please forgive me, I was wrong, I won’t do it again

No time to put a towel over my face and pour water from a pot

No handcuff or strap

Every night I read my country’s history of torture

Then in the morning I open the window and sing loudly at the roofs below the mountain

How could I possibly forget this place?

I have Pig who needs to be rinsed with a song then go

Dear Song, Please stay stuck to my body for 12 hours

A horde of healthy pigs like young strong men get thrown into the pit

They cry in the grave

They cry standing on two legs, not four

They cry with dirt over their heads

It’s not that I can’t stand the pain!

It’s the shame!

Inside the grave, stomachs fill with broth, broth and gas

Stomachs burst inside the grave

They boil up like a crummy stew

Blood flows out the grave

On a rainy night fishy-smelling pig ghosts flash flash

Busted intestine tunnel their way up from the grave and soar above the mound

A resurrection! Intestine is alive! Like a snake!

Bloom, Pig!

Fly, Pig!

Boars come and tear into the pigs

A flock of eagles comes and tears into the pigs

Night of internal organs raining down from the sky!

Night of flashing decapitated pigs!

Fearful night, unable to discard Pig even if I die and die again!

Night filled with pig squeals from all over!

Night of screams, I’m Pig! Pig!

Night when pigs bloom dangling-dangling from the pig-tree

What do we think of Hyesoon’s poem?

Does it build a solidarity between experiences of oppression and abjection,

experiences that take place both within the world and within language, across

the human and the animal? Could Hyesoon’s practice be usefully described as

feral? What makes it so?

*

And here arrives another seamless segue: an extract

from John Berger's 1980 essay 'Why Look At Animals?':

To suppose that

animals first entered the human imagination as meat or leather or horn is to

project a 19th century attitude backwards across the millennia. Animals first

entered the imagination as messengers and promises. For example, the

domestication of cattle did not begin as a simple prospect of milk and meat.

Cattle had magical functions, sometimes oracular, sometimes sacrificial. And

the choice of a given species as magical, tameable and alimentary was

originally determined by the habits, proximity and “invitation” of the animal

in question.

Here's the full thing, and well-worth

the read:

file:///C:/Users/onlye/Downloads/Berger_Why_look_at_animals.pdf

We don't have to accept Berger's statement wholesale, especially if we think

about the magical and instrumental properties of an animal as being more

closely related than he seems to suggest (i.e. perhaps cattle became endowed

with magical significance precisely because human beings depended on them in so

many practical ways), but I decided to share this quote because I think the

idea of a ‘magical’, ‘sacrificial’, or ‘oracular’ way of understanding

the animal is one way of accessing the feral. And I wanted to introduce the

idea that although a poem might replicate or comment upon the ‘contest of

mastery’ or the unequal dynamics implicit in animal-human relations, it might

also offer us a way of resisting this idea.

To which end, this gorgeous

shape-shifting poem by Daria-Ann Martineau:

Carnivorous, with a varied and opportunistic diet

2020

Call me lagahoo, soucouyant. Call me other.

I came ravenous: mongoose consuming

fresh landscapes until I made myself

new species of the Indies.

Christen me how you wish, my muzzle

matted with blood of fresh invertebrates.

I disappear your problems

without thought to consequence.

Call me Obeah. Watch me cut

through cane, chase

sugar-hungry rats. Giggling

at mating season, I grow fat

multiples, litters thick as tropic air.

Don’t you find me beautiful? My soft animal

features, this body streamlined ruthless,

claws that won’t retract. You desire them.

You never ask me what I want. I take

your chickens, your iguana,

you watch me and wonder

when you will be outnumbered.

My offspring stalking your village,

ecosystems uprooted, roosts

swallowed whole.

I am not native. Not domesticated.

I am naturalized, resistant

to snake venoms, your colony’s toxins—

everything you brought me to,

this land. I chew and spit back

reptile and bird bone

prophecy strewn across stones.

What I like about this poem is that the speaker mocks the attempts of the addressee to map categories of identification or status onto her ever shifting form. She is one minute an animal, then a human, then a plant, then a supernatural entity. This suggests that the frictionless distinctions we draw between these categories are, at best, grossly oversimplified, worse, fictional, illusory. When the speaker states: ‘I am naturalized, resistant/ to snake venoms, your colony’s toxins—/ everything you brought me to’ she signals the sorry history of colonial conquest, but also, I think, how a neat distinction between the natural and the man-made is now largely impossible: human beings are making changes to the biosphere that will be preserved in the geology, chemistry and biology of our planet for thousands or even millions of years. We are entering a period of unprecedented and catastrophic ecological crisis. And the scene of writing is not somehow magically immune from this changed dynamic between “civilization” and the natural world. This poem advocates for adaptation and evolution, and for hybridity and ambiguity as mechanisms of survival. I love this poem’s darkly triumphalist tone. It is a warning: that which colonisers think they change can end up changing them just as surely. With pressure, the colonized person, or animal, or land, or language becomes stronger, more resilient, more capable and inventive.

Martineau's poem is still staying within the bounds of the free-verse lyric form, using a (relatively) stable speaking subject in a project of direct and urgent address to an accused other. This feels important and necessary for this poem: it draws a parallel between the physical body of the colonised ‘other’ and the textual body of the poem. This implicates literature and the act of writing in the process of colonisation. It reminds us of the risks and consequences of words.

*

And this seems like a good moment to offer an interjection about lyric practice in general, and the scope and limits of poetic (ecocritical) innovation, particularly with regards to the feral.

Specifically, I'm wondering about work that derives its potency and heft from a collision of the pure and profane, of 'nature' and its abused survivals. There's a suggestion within these kinds of image that something does not quite belong, that there is matter out of place, that a boundary has been transgressed. The problem with the feral is that it is equally at home in the landfill or the sewer. Waste is so often conceptualised as unwanted, discarded, leftover and useless, yet there are categories of both human and animal life (hyenic scavengers, gulls, waste-pickers) who disrupt the idea of trash as the mere inert residues of consumer society. Scavengers and synanthropes make trash come alive, part of a 'mutable, transnational, temporal process by which humans, to greater and lesser degrees, recognize and extract value and utility from matter. And as a process, trash is interwoven with rapid urbanization, energy consumption, climate change, international movement of toxics, and other major environmental challenges of our time' (Ted Mathys, 'Wastepickers and the Seduction of the Ecopoetical Image' in Evening Will Come: A Monthly Journal of Poetics (Trash, Issue 37, January 2014).

Something to think about, anyway. And here I'd like to introduce the idea of the 'necropastoral' with a quote from the essay 'What is the Necropastoral?' by Joyelle McSweeney:

The Necropastoral is a political-aesthetic zone in which the fact of mankind’s depredations cannot be separated from an experience of "nature" which is poisoned, mutated, aberrant, spectacular, full of ill effects and affects. The Necropastoral is a non-rational zone, anachronistic, it often looks backwards and does not subscribe to Cartesian coordinates or Enlightenment notions of rationality and linearity, cause and effect. It does not subscribe to humanism but is interested in non-human modalities, like those of bugs, viruses, weeds and mould […] The Necropastoral is literally subterranean, Hadean, Arcadian in the sense that Death lives there. The Necropastoral is not an "alternative" version of reality but it is a place where the farcical and outrageous horrors of Anthropocenic "life" are made visible as Death. […] The obscene: that which should be hidden away but forces its way through the membrane. Obscene event = Apocalypse…

Here's the full essay:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2014/04/what-is-the-necropastoral

We'll be returning to the necropastoral next week, but for now, here's a brief summary and food for thought for the final poem of the session: if pastoral poetry is concerned with an idealised depiction of nature, with the aim of moral or spiritual improvement, then the ‘necropastoral’ says that a jolt of fear or discomfort can be far more effective than romance in motivating change. Necro, of course, comes from the Greek nekros, meaning death or corpse. The necropastoral invites us to imagine a landscape filled with dead bodies, enslaved bodies, diseased bodies, mutilated bodies; worms, rats, cockroaches, rabid animals, decaying trees, polluted rivers, smog, rotting food, ruins, and blazing wildfires. The necropastoral repurposes or subverts the aims of the traditional pastoral, by forcing us to look at blighted nature, to consider sin, evil, fear, and destruction so that we might reflect on our mortality, morality, and ethics.

For McSweeney, our political calamites are inseparable from those that decimate the natural world. Which means that we, as poets, can not write as neutral, outside observers to the unfolding ecological crisis. It also means that we have an ethical imperative not to conceal or to beautify. McSweeney’s work is against the notion of catharsis and consolation, as a refusal of reality, a kind of letting-off-the-hook or willed inattention to what’s going on around us. She states that the necropastoral is ‘The lethal double of the pastoral and its fantasy of permanent, separated, rural peace. In emphasising the counterfeit nature of pastoral, the necropastoral makes visible the fact that nothing is pure or natural, that mutation and evolution are inhuman technologies, that all political assertions of the natural and the pure are themselves moribund and counterfeit, infected and rabid.’

Necropastoral poetry then is a space in which death and damage are viscerally visible, and in which we are entangled with nature, a nature that is ‘poisoned, mutated, aberrant, spectacular, full of ill effects and affects.’

Sounds like a hoot? Wait until you get a load of the final poem. In the session we looked at 'RENDERED' from The Cow by Ariana Reines (Fence Books, 2006), and I'm providing a link to the full text here (excuse the crappy quality of the scan, but I think it's still legible):

In her essay on The Cow, Daisy Lafarge writes about how certain kinds of poetry might offer spaces of criticism, not only of society, but of poetry itself:

In a poem, the body of the animal can only be conjured by the poet, and is subject to their (anthropo-) perspective, objectified in writing to illustrate a point, or else fetishized in metaphor, hollowed out as symbolic vessel in which something else can be smuggled – whether that be emotion, event or a part of the poet’s own psyche. This ‘exploitation’ is so much the lifeblood of poetry that it goes largely unchecked; any semi-fluent reader knows that Hughes’s crow, Blake’s tyger and Coleridge’s albatross amount to ‘more’ than zoological studies.

What poetry can do is ‘name and lay bare’; the damage done to animals in such a way that the reader is forced to recognise their own complicity. There's a pact, in a great deal of lyric poetry, between writer and reader, to uphold the animal as a metaphor. But what happens when a writer strives, as Reines does, to move beyond metaphor, to – as she puts it – ‘get to the other side of the animal’?

The Cow’s approach to the animal is intensely aware of the overlaps and gaps between how animals are treated by both the ‘machinery’ of poetry and that of the global meat industry. The book performs a kind of critique of how the animal is used as a linguistic figure, an edible resource, and a source of capital. I think Reines is also exploring the association between women’s bodies and animal bodies – as objectified and consumed by men.

‘Cow’, of course, is a loaded word within English. We might usefully ask ourselves if the poet can ever escape the weight of associations that accrete around the bovine as metaphor. Even when attending to the suffering of the literal animal, is a cow ever just a cow?

The Cow looks at the instrumentalisation of animal and human bodies in a system – namely the late-stage capitalist patriarchy – that does not regard either as worthy of care or preservation. This disregard is a process the environmental and feminist philosopher Val Plumwood, writing in Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (Routledge, 2003), refers to as ‘backgrounding’. It amounts to:

making the other inessential, denying the importance of the other’s contribution or even his or her reality, through mechanisms of focus and attention.

We can refer this back to the idea of disenchantment and rationalisation, the same process taken to its logical conclusion.

The Cow asks what comes of the attempt to foreground the animal. Although we exist in a time in which the rights and agency of nonhuman subjects are being theorised and considered more than ever, these same candidates are simultaneously subject to increasing exploitation and destruction at human hands. Reines’ book frames lyric lines within the clinical language of a livestock manual. The poems focus on ‘abjection, female filth and the damage we inflict on animal bodies’, shredding texts and physical forms alike, fusing and remixing human and animal identities, registers and lexicons, playing feminine artifice against the clinical language and graphic descriptions of guidance texts for the practice of butchery:

Boys rinse their / arms in what falls from my carotid. My body is the opposite of my body / when they hang me up by my hind legs.

In The Cow, woman and animal speaker are conflated; textual body and brutalised animal body are merged. In the poem ITEM, the reader is told that the omasum (the third part of a cow’s stomach) ‘is also called “the book” owing to its many leaf-like folds’. At one point Reines asks:

What happens to the world when a body is a bag of stuff you can empty out of it.

Errors, musculatures.

Can I empty language out of me.

What difference does it make how a thing dies. Consciousness. Nobody knows

what that is…

*

All of which would seem to be enough to be getting on with. So I'll leave you with this week's prompt: write a poem about a blighted or deadly landscape from which animal life has been - or is being - expunged, and human habitation is becoming increasingly vexed. Or write a poem about how animals and/or humans find ways to exist in these blasted landscapes. Please send me the results, and feel free to bring them to the workshop next week!

.jpg)